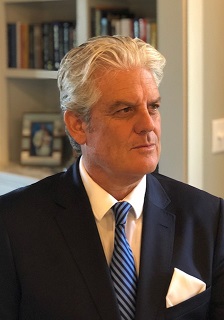

From the CEO – October 2021

Dear Clients,

Dear Clients,

One of the major developments this week on the international stage is the COP26 summit in Glasgow. As is well known, the summit is designed to bring together parties to accelerate collective action towards the goals of the Paris Agreement and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

The sequencing aligns with the recovery of most nations from the effects of the pandemic with the overarching goal of reducing global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius by the middle of the century. The idea here is to achieve the ‘net-zero’ effect: viz., produce less carbon than is taken out of the atmosphere. There are other broadly-related goals on the agenda, from working to respect natural habitats, to mobilizing finance to address climate change to the tune of $100bn annually.

The conference extends from 31 October to 12 November and, as par for the course in these events, the usual array of ‘quasi-challenges,’ and finger-pointing has commenced: the UK’s Boris Johnson reportedly used a James Bond analogy to drive the point home of the severity of climate change (viz., 007 being strapped to a doomsday device that is ticking towards detonation), adding that the ‘anger and impatience’ of the global community would be ‘uncontainable’ if the world’s leaders didn’t take decisive action this time around.

Similarly, European Commission president, Ursula von der Leyen, singled out China and Russia for their failure to physically attend the Glasgow meetings. Italy’s prime minister, coming off the G20 summit in Rome, sounded a more optimistic tone by suggesting that the two conferences show that multilateralism is back on track as an organizing feature of global affairs (presumably after the neglect it suffered under Trump’s leadership in the US), although most would conclude that the Italian politician’s conference on the Tiber resulted in a diluted final communique that largely repeated existing targets and broke limited new ground.

To be sure, the summit has just begun, so excessive skepticism should be curtailed. Indeed, some nations have put forward some respectable goals. Both India and Vietnam pledged their own set net-zero targets; Brazil offered a way forward, which is helpful given the country’s sometimes lagging response to environmental concerns; and some 80 nations have signed up to The Global Methane Pledge – a collective promise to cut emissions of methane by 30% by the end of this decade.

Yet notwithstanding the political posturing, the tabling of plans and initiatives, final communiques, and such, in the end the success of these summits – and the various policies that might be forged later – is slightly more nuanced and depends largely on the policies themselves. Politics at the local and national level is important; so too are the ways in which the policies are constructed and the environment in which they are promulgated.

This was made clear in a recent IMF Working Paper, titled “Are Climate Change Policies Politically Costly?” In this piece, the authors use our ICRG index of popular support from 34 developed and emerging economies from 2001-2015, along with the OECD’s ‘Environmental Stringency Index’ to show that the success of climate change policies resides largely in their design along with a range of internal and external factors.

Among the findings is that – and I urge readers to have a look at this entire study since it is rich in methodological issues and in the review of the relevant literature – only market-based Climate Change Policies (CCPs), such as emission taxes, generate negative effects on popular support. Non-market-based policies (such as emission limits) do not pose significant political costs. The problem is such policies are often less effective in achieving their goals.

Moreover, the internal and external environment matters. Timing is important since the political costs for increased environmental regulation are greater when energy prices are higher for households. CCPs also tend not to fly in countries with a ‘high input share’ of ‘dirty energy’ in mining and production. And executing an effective menu of CCPs is limited when inequality runs high and when forms of social insurance are lacking or inadequate.

These conclusions are quite intuitive, but they also inject a measure of realism into some of the loftier goals of politicians and bureaucrats. They offer an empirical explanation of why so little apparent progress has been made to tackle climate change. If anything, the findings suggest some conditions for complementary policies for governments to consider when forging ahead with their own set of CCPs.

* * *

In other news, I’m happy to be speaking again on a more frequent basis with students of geopolitical risk and emerging markets. Over the next couple of weeks, I’ll make a return visit with Professor Steven Johnson’s political risk class at American University; I’ll offer some thoughts and engage in a dialogue with Peter Marber’s emerging markets class at Harvard University; and schedule a return date with Professor Susan Schroeder’s’ political risk group at Sydney University.

While working through the logistics of delivering a keynote address on corruption and economic growth to a gathering in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in early December, I was also pleased to participate in a very informative event for the diplomatic corps based in Kazakhstan, titled: ‘Implementation of the Anti-Corruption Policy: Progress and Prospects.’ Quite notable efforts are being implemented. Inter alia, the extent to which all public services have been digitalized/available online is instructive.

New and existing clients should note that we have released a brand-new addition to our popular Researchers’ Dataset series to complement the other data bundles announced this year affecting ESG, corruption, and internal/external conflict. The new series will offer clients a more granular look at the political risk components of the ICRG, supported by 20 years of monthly data. Scores of academic studies have been conducted using this series, providing unique insights in asset volatility, government responses to the pandemic, and many more. Contact us for more information.

Our new book Quid Periculum? Measuring & Managing Political Risk in the Age of Uncertainty, co-edited and co-authored by Peter Marber (Harvard/Aperture Investors) continues in high demand. The book includes such diverse topics as risk forecasting techniques, reliability measures, the impact of political risk on asset prices and sovereign debt workouts. Also featured is a special roundtable discussion by some of the world’s leading voices in the field on the future of political risk, who combine to address some of the challenges presented by globalization and COVID-19.

October was another productive month for new and returning clients, ranging from some of the world’s top universities to the largest institutional investors throughout the US, Europe, the UK, and the Middle East and Asia. Our data are now regularly featured in the research of the IMF, Bank for International Settlements, and various central banks, such as the Bank of Italy.

The new look of PRS is coming soon, too. Paying homage to our roots in the Hindu Arabic number system of the Renaissance period to more recently in the behavioral revolution of the late 1960s, one of our new features will be a regular podcast series, featuring interviews and discussions with some of the most distinguished practitioners and academics in the field of geopolitical risk, from such places as Saudi Arabia, Uzbekistan, the UK, and Dubai. No other podcast series will offer such depth, relevance, and intellectual sophistication. Stay tuned.

Finally, ICRG and related PRS data continue to be the gold standard of all geopolitical risk data among the scholarly and research communities. For example, with the recent discussions about the IMF and its latest revisions to growth and warnings about inflation, a recent Bank of Italy Working Paper queried whether the size of the Fund’s lending capacity and the introduction of the new precautionary facilities play a role in explaining emerging market countries’ spreads. Using our ICRG data in part, among the findings: what appears to matter most to spreads are the overall resources available for lending by the Fund, as opposed to the channels through which such resources can be accessed by members. (https://lnkd.in/d2BWbhFS)

Additionally, another recent study, appearing in the IMF’s Working Paper series, uses ICRG data in part to show that economies where leftist governments are more often in power face worse borrowing terms due to higher default risk, a greater reluctance for fiscal austerity in bad times, and a higher share of government spending on average. (https://lnkd.in/dcjjBdza)

Thanks for your continued support, and please contact us if we can be of any assistance.

Chief Executive

PRS INSIGHTS

Moving beyond current opinions, a seasoned look into the most pressing issues affecting geopolitical risk today.

EXPLORE INSIGHTS SUBSCRIBE TO INSIGHTS