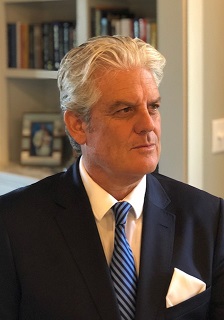

From the CEO – March 2020

Dear Clients,

There is really no escaping the pressure to write about the pandemic that has now affected some 200 countries and especially those with densely populated areas. But rather than rehashing case statistics and related items – other sites do a better job – I’d like to address the impact of the virus from a future geopolitical risk perspective. Where we are now? And what might the future risks resemble?

I’ll also comment on such ideas as Black Swans and White Swans and offer some thoughts on dealing with the overall uncertainty borrowed from Michel de Montaigne and the Stoics.

To be sure, the impact of the coronavirus on future business and investment landscapes, the global economy, and on the nature and scope of geopolitical risk will be significant and longstanding. Despite the recent efforts of governing authorities in many developed and emerging markets to inject liquidity into the financial system, backstop asset values, and cushion the blow to business and workers, there will be a fallout: From higher sovereign and corporate debt levels, servicing costs and defaults, to a higher risk of repatriation and payment delays. Lower credit quality, uneven growth, inflation in some quarters (agriculture), and prolonged uncertainty over a range of asset values (real estate) should also be prevalent. On the social side, the future will likely see rising incidents of joblessness and inequality, pockets of social turmoil, and increased demands on the government from civil society that will be challenging to address.

There has been some discussion about the virus being the Black Swan of 2020 – the event that brought down the market (and economies) that very few, if any, could see coming. A surprise event, as it were. The reference – as we all probably now – was popularized in an excellent book by the same name by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in 2007. I recall reading this one that summer/fall on a Vancouver beach just as concerns over the sub-prime mortgage crisis and fallout was on some people’s minds.

What we are seeing is anything but a Black Swan. In Taleb’s book, a pandemic of this sort was mentioned as a White Swan – something that would occur in the future with a considerable degree of probability. Despite warnings over the years, governments and others are now playing catch up with the rising number of cases and the resultant stress they are putting on available resources (the exception here seems to be South Korea that reportedly prepared for this event over a decade ago, and which seems to have successfully ‘flattened the curve’). Some nations appear to be in the relative early stages of the pandemic (US), while others seem to see some easing in the number of new cases (Italy). In New York City, which is one of the ‘hotspots’ for the spread of the virus in the US, the estimate at this point is that the rate of hospitalizations will peak in several weeks’ time.

There is an end in sight. But much like the world changed after 9-11, the coronavirus has changed the world. Similar to 9-11, all of us will adapt and move on. Better days are ahead.

One of the advantages we have as a firm in the geopolitical risk and forecasting field for over forty years is that we have been through turbulent times before: from Black Friday in 1987, the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997, the dot-com burst, September 11th, and the 2007-08 Financial Crisis and Great Recession. We weathered each of these crises as a firm, helping our clients through the various risk pitfalls, with the benefit of the longest and most comprehensive geopolitical and country risk data series in the world. These same data have been continuously and independently back-tested for accuracy and relevance for over 25 years.

So looking ahead, and judging from the March data of the International Country Risk Guide (ICRG), some additional and general observations can be made about the risks that await once the pandemic eases to the point where it is manageable.

1/ Borders and regulations will matter more than ever before, with a much more cohesive relationship developing between large firms and the government to deal with supply chains, markets, debt and debt servicing issues, among other items. Nationalizations and significant government ownership of key industries look more likely. Health care, accessibility, joblessness and inequality will dominate policy discussions in many countries, especially those that were not adequately prepared for the pandemic and that were the hardest hit.

2/ Government financial support for ailing firms will continue, elevating discussions about the nature and scope (and propriety) of such actions. Budget surpluses will be hard to achieve in the near-term. Tax regimes will be adjusted, and rates will rise in many now lower-taxed nations.

3/ Incidents of social turmoil will likely rise, suggesting increased government instability, uneven policy responses, populist politicians, and an increased role for security forces.

It bears mentioning again that these events are now showing up in our risk data, with Latin America and parts of Africa being the most susceptible to a significant rise in cases in the near- to medium-term. Indeed, the virus has caused such significant disruptions, that roughly 80% of the countries covered in our universe of 140 countries had their political risk profiles adjusted, accounting for over 150 individual political risk metrics being altered. This is the largest monthly change in ICRG’s 40-year history!

As many know, I tend to read much from French and Italian writers from the past. By connecting with the past, I’m helped make sense of the present. The writings are also a literary refuge of sorts in a time when we are inundated by non-vetted information and opinions online.

Michel Eyquem de Montaigne’s work, the Essays (1580), has some currency at this time. A significant literary figure during the final stages of the French Renaissance, and noted by some as the father of modern skepticism, Montaigne suggested we accept fear and uncertainty for what it is, which is present and not to be shunned. But Montaigne also spoke about the need to create diversions from our worries. At the present time these could range from spending more time with loved ones and eating healthy foods and exercising as much as possible. When combined, we will be in a better position to understand ourselves, our nature. He put it (mildly) in this passage toward the end of the Essays:

“It is an absolute perfection and virtually divine to know how to enjoy our being rightfully. We seek other conditions because we do not understand the use of our own…Yet there is no use our mounting on stilts, for on stilts we must still walk on our own legs. And on the loftiest throne in the world, we are still sitting only on our own rump.”

To this extent, Montaigne borrowed heavily from the Stoics, especially the works of Seneca. Generally, for the Stoics, happiness was about living in the present as much as possible, enjoying what is before us. A heightened sense of consciousness, as it were. Worries about the future were time-consuming, most of all, and generally out of our control. It was about enjoying life as we have it, now, or as Seneca put it: life is like water that is flowing through our fingers. The flow cannot be stopped. But we can drink deeply from it while it lasts.

Thanks for your continued support. Keep well and keep safe.

Chief Executive